by Dr Linda King

Objects prompt memories. They help us understand who we are, where we’ve come from and what we might be. Through them we remember loved ones, precious moments, significant events. They speak to both personal and collective histories.

We have had museums for centuries and these are full of objects. These institutions display the choices of experts (historians and curators) outlining what the public should consider as important. National Treasures has put the selection of significant historical objects in the hands of the public. It therefore provides the opportunity to re-evaluate how our history has been presented and recorded.

Designed objects: society’s ideas in physical form

As a design historian I research and write about mass manufactured objects. These objects are created to be useful, are made in multiples (as opposed to being one-off items), are popular and commonplace. They reflect the everyday experiences of ordinary people.

Almost everything we use or come in contact with has been designed: from books to websites, clothing to jewellery, furniture to household utensils. Through examining these objects – their shape, decoration and materials – and what they symbolically represent, we gain insight into the interests of any society at any particular moment. Designed objects reflect larger cultural concerns and interests. They are literally ideas in physical form.

Ireland’s relationship with design is very different to that of other western countries. Design develops in tandem with industry (physical or technological) and until relatively recently the main industry in Ireland was agriculture. Coupled with centuries of political instability, this unique set of circumstances has meant that many of our indigenous design industries were slow to evolve.

Yet, National Treasures received a great many designed objects from the small and ubiquitous (stamps, coins, books, record covers, ceramics) to the large and imposing (bikes, computers, furniture). I am particularly interested in how our examination of such objects can be used to expand (and sometimes challenge) our collective history. National Treasures provided many opportunities to do just that and I have selected a number of objects here that speak to this theme.

I have a particular interest in the histories of graphic design, travel, tourism, and technology because these are subjects that everyone can relate to. I am also interested in objects that reveal stories about women’s experiences because all too often history (comprising the words ‘his’ and ‘story’) is male authored and focused.

Objects representing all these areas were kindly submitted to National Treasures and for me, the most interesting examples were those that told multiple stories: the personal, the collective, the idiosyncratic, the under-valued, the neglected.

Designing for travel and tourism

One such example is the Aer Lingus travel bag owned by Frank Aiken while he was Minister for External Affairs (1957-69). This is a family-owned object, of deep personal significance, but reveals a much broader story of national significance.

Aiken’s cabinet colleague, Seán Lemass, founded the national airline in April 1936, with one plane that linked Dublin to Bristol. In the early decades of Irish independence, Aer Lingus was the most potent symbol of political sovereignty and infrastructural modernisation for both Irish and international audiences. Aer Lingus’s symbolic role as a ‘flag carrier’ was conveyed visually and through design: in the huge logos on the tailfins of its planes as they crossed the skies or sat on the aprons of airports, through its cabin crew as they proudly wore their uniforms, through its advertising and its publicity that hung in travel agents around the world.

This bag dates from between 1962 and before Aiken retired in 1969. We can tell this because of the version of the logo that is being used. This comprises a shamrock (against a background of six stripes), a plane, and the name of the company in italicised typography. The logo is typical of its time: combining recognisable symbols of flight (the plane), slanted letterforms (to convey movement) and a localised reference to ensure the country of origin is clear (the shamrock). In size and style, this bag is similar to those given out by all airlines at the time to valued customers. It is plastic, would have been cheap to manufacture, and is one of two identical bags submitted to National Treasures. However, with this particular example, its importance lies in its symbolic value as linked to Irish politics.

Aer Lingus launched its transatlantic route in 1958, which was a monumental achievement for the country. Aiken regularly used this service and the bag is a reminder of his work at the United Nations in New York and through him, Ireland’s substantial impact on world politics. For Aiken this was a utilitarian object, used to carry the newspapers he read while travelling from Dublin to New York. Yet, he wrote his name on it – as Gaeilge (PMcA) and in pencil – so it was clearly an object that he valued.

The bag encourages us to think of multiple stories: of the political achievements of one of the colossuses of Irish politics, of the development of Irish commercial aviation, of the political instrument that is a national airline. Submitted by Aiken’s son – also Frank – it is also a deeply personal family momento, a reminder of a father going to work who just happens to have the most extraordinarily influential job and a transatlantic commute to the office.

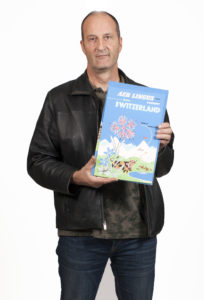

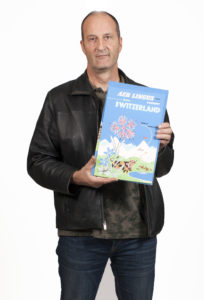

Dutch designer Jan de Fouw’s sketches for a series of Aer Lingus posters are also dearly cherished family-owned objects. They were submitted by de Fouw’s son, Jan, and also reflect broader stories tied to the national airline.

De Fouw arrived in Ireland in 1951 to work on advertising for Aer Lingus, having previously worked in the publicity department of KLM. Throughout the 1950s, the airline expanded its route network to capitalise on the number of Americans travelling to Europe. As the Irish government slowly moved from protectionist economic policies to greater engagement with the international community, the development of tourism was seen as critical for Ireland’s economic survival. The success of Aer Lingus in this context was dependent on a clear and engaging publicity strategy. At the time the Irish graphic design and advertising industries were not as developed as in other countries, so a decision was made to import this expertise.

These small sketches were hand-painted in gouache and would have been presented to the company’s publicity department for approval. After a selection was made the final poster was screen-printed and distributed to travel agents and tourist bureaux. These examples advertise travel to Switzerland and date from 1957. With their colourful, modernist European and US-influenced graphic style, the finished posters supported much needed tourism development and offered a window onto a (largely) unobtainable and glamorous world for a contemporary Irish public struggling with severe economic challenges.

De Fouw subsequently worked for other tourism-related companies including Bord Fáilte and John Hinde. He was one of a generation of Dutch designers that worked in the Irish graphic design and advertising industries and collectively they had a huge impact on how Ireland was visualised as a tourist destination.

So these sketches also embody many interconnecting stories: the development of Irish tourism as supported by the airline, the growth of Irish graphic design and advertising, and the impact of immigration on the development of Irish design generally, a theme that is present in a number of other National Treasures objects (including the Waterford Crystal bowl submitted by Ivana Bacik and the Crannac Chair submitted by Alex Lloyd).

Designing for religion and school

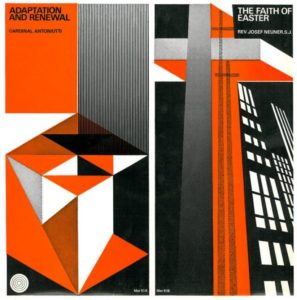

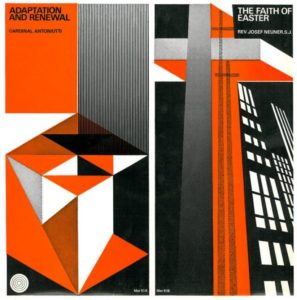

The album Adaption and Renewal/The Faith of Easter (1969) – submitted by Brian McMahon – was also designed by Dutch immigrant graphic designer. Cor Klaasen designed a series of thirty LPs of Catholic sermons and spoken word, released by the Mercier Press in Cork (1967-71). These recordings, by liberal Catholic clerics, show the Church using the contemporary technology of vinyl records to spread its doctrine at a time when Catholicism was very much ingrained in the daily life of most Irish citizens.

The album cover’s abstract illustrations in black, white and orange would be striking in any context, but here this graphic modernism is used to visually represent a modernising Catholic Church in the wake of Pope Paul VI’s Vatican II (1962-65) reforms.

Klaasen’s name may not be widely known but his work is recognisable to generations of Irish people who were in secondary school between 1969 and 2000. He designed covers for many school textbooks including the poetry anthology Soundings, an example of which was submitted to National Treasures by Fintan O’Higgins. The cover of this book again uses an abstract, graphic modernism to represent the intangible (the spoken word). So many of us read this book on an almost daily basis, scribbled notes in its margins, probably loved and loathed it in equal measure. With the benefit of hindsight (and more than a little nostalgia) it reminds so many of us of our school experiences and due to popular demand, Soundings was reissued in 2010.

Klaasen designed many other books for the educational publisher Gill and Macmillan (including the prose anthology Exploring English) and his work demonstrates how designed objects are at the very heart of everyday Irish life.

Designing for and by women

These examples of are only some of the many objects submitted to National Treasures that shed light on lesser-known aspects of Irish culture or offer alternative interpretations of our collective history. On many occasions the project reminded how the experiences of Irish women are central to understanding much broader national stories.

A case in point is the electric ironing board, an object that was handed down to Siobhan Long by her mother and is still used on a daily basis. It was a prize in a baking competition in the 1960s, sponsored by AET of Dunleer, County Louth. This indigenous company that no longer exists, but at the time it was Ireland’s largest domestic appliance manufacturer. Again this is a very personal object but it points to a much bigger story of infrastructural modernisation and its impact.

The hydro-electrical station at Ardnacrusha in Co. Clare had been completed in 1929 and the Rural Electrification Programme was rolled out nationally between 1946-79. In 1946 only one in three homes in Ireland had electricity and to encourage its use, the ESB and the manufacturers of domestic appliances, regularly held such competitions awarding prizes of ironing boards, hair dryers and other electrical devices.

An ironing board would have been a novelty at the time, but this one is even more so as it plugs into the mains and the iron is placed on it to heat. On one hand it points to a typical domestic experience to which many can relate. However, it also reveals much bigger stories: the spread of electricity throughout Ireland from the 1950s onwards; electricity’s modernisation of the Irish home; forgotten Irish industries; and the use of such competitions to showcase the household management skills of future wives. Such competitions emphasised society’s expectation of Irish women. This, for example, was divided into two categories of participants: ‘single women’ of 17-25 and ‘married women’, each given different baking tasks to prove or confirm their competencies.

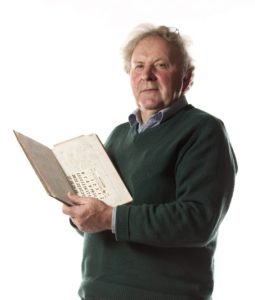

In the 1960s the ESB sponsored the television show of Ireland’s first celebrity cook, Maura Laverty. At the time Laverty’s cookbook Full and Plenty (1960) was very popular and became a standard text used in schools as part of the domestic science curriculum. The National Treasures copy was originally a schoolbook and was submitted by its owner Mary Morrissey. Her mother subsequently used it, inserting additional recipes between its pages.

Full and Plenty opens with the line ‘cooking is the poetry of housework. It combines household management advice with fiction and memoir, reflecting the fact that Laverty was a journalist, novelist and scriptwriter (she wrote Ireland’s first soap opera, Tolka Row). Recipes, including those for stew, soda bread and boxty, were interspersed with satirical stories of women securing husbands through their culinary skills. Colour photographs of the final dishes, and black and white illustrations of ingredients and kitchen utensils, pepper the pages as visual references. The book also became a key reference for those, and there were many at the time, running a household on a tight budget.

From 1961 the ESB also sponsored the annual Ploughing Championships. This was designed to encourage the electrification (and thus modernisation) of farming, A rubber and glass breast pump manufactured by Fannin and Co, a medical supplier on Dublin’s Grafton Street, also indirectly references farming. Submitted by Eithne Lynch and used between 1921 and 1931, it enabled Eithne’s grandmother – who married a farmer – to juggle the task of rearing a young family with keeping on top of her farming commitments.

On one hand it’s an example of an early Irish medical device and demonstrates design entrepreneurialism. But it again encourages us to think about national stories: about how a technology derived from dairy farming was adapted to human usage, about how the introduction of such devices to express breast milk saved the lives of children separated from their mothers, of how the balance of family and work life that women still struggle with today has a earlier precedents.

The employment experiences of Irish women outside the home or farm need greater analysis and consideration. Barry Curtin’s War of Independence grenade shell, for example, points to a discrete chapter in Irish history within which women were central. The bomb was manufactured from a mold subversively made at the Ford factory in Cork. The factory had been established in 1917 and was one of Cork’s biggest employers until it closed in 1984.

This grenade shell would have been filled with explosives, held in place by a trigger pin. Its shape was based on a design patented by grenade designer William Mills in 1915, who was working at the Mills Munition Factory in Birmingham. Its distinctive and deep exterior grooves provided a secure grip for those that used it and it was widely used during WW1. The men who made the mold for the shell were Ford factory employees. They are thought to have used their knowledge of casting car engines in the production of this weapon. This may well be the case but the main source for bomb-making knowledge in Ireland during the revolutionary period came from women.

Five British War Department munitions factories operated in Cork, Dublin, Galway and Waterford, supplying British troops during WW1. In addition, there were many other privately owned munitions factories dotted across the country, including in Cork. The workers in these factories were mostly female and working class. They were often referred to as ‘Bomb Girls’ and during the War of Independence they liberally shared their expert knowledge of making explosives and weapons with Irish revolutionaries. Therefore, women were at the heart of the guerrilla activity that defined the period from 1919-21 and it is likely that the men casting these grenade shells were reliant on their knowledge.

Final thoughts

These designed and mass-manufactured objects reveal only some of the many discrete or hidden stories that National Treasures has unearthed. As a design historian this has been a dream job: I’ve met amazing people who have generously shared their stories and given insight into our collective cultural history as told through the objects they cherish and hold dear. Through these personal mementos National Treasures has offered many opportunities to look at how our history as a nation has been captured, to note the gaps in our collective knowledge and to think about how we might add to our history in the future. These objects are literally the fabric of our society.

Dr. Linda King lives and works in Dublin. She is a design historian at IADT, Dun Laoghaire where she is also Co-Programme Chair of the BA in Visual Communication Design. Linda has published and broadcast widely on various aspects of Irish design and has been a consultant on design issues to many organisations including Dublin City Council, the Design and Crafts Council of Ireland and the National Archives (UK). In 2011 she co-edited the first substantial survey of Irish design: Ireland, Design and Visual Culture – Negotiating Modernity, 1922-1992, a book that examined how designed objects were used by various governments to visually and physically endorse state policies. Linda previously worked at the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York and is currently Visiting Professor in Design and Irish Studies at Concordia University, Montreal.

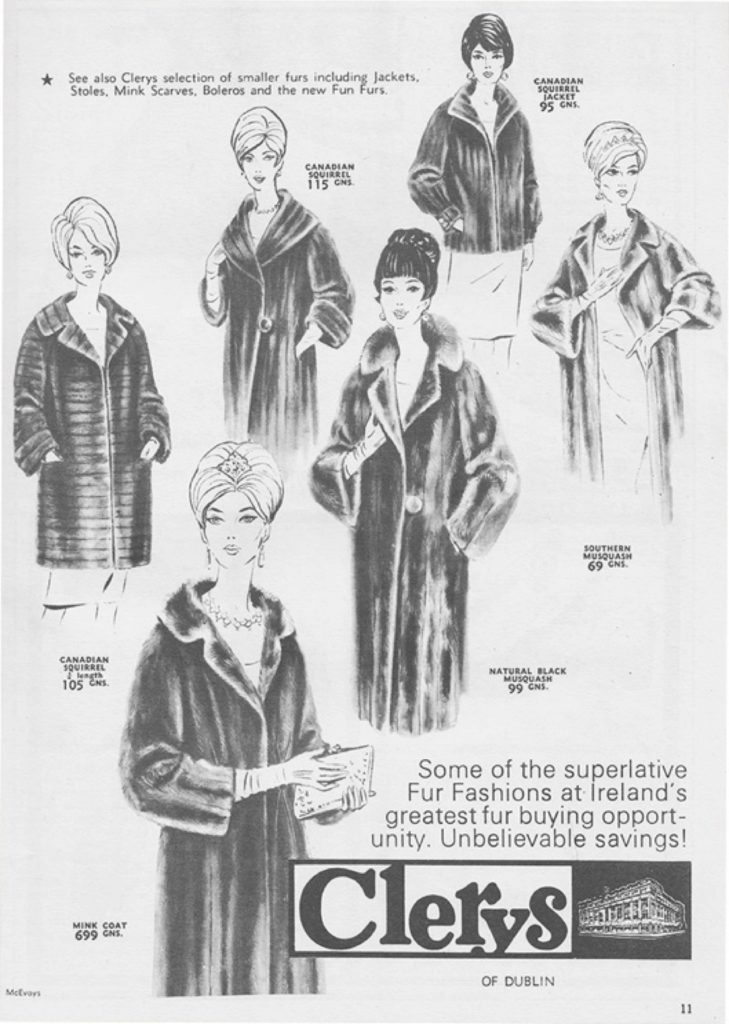

Fur was the epitome of glamour in mid-twentieth century Dublin. Here Clery’s advertise some ‘superlative fur fashions’. Mrs Vickers mink coat was a key item of her wardrobe which she wore the Clery’s ballroom in the 1950s and 1960s.

Fur was the epitome of glamour in mid-twentieth century Dublin. Here Clery’s advertise some ‘superlative fur fashions’. Mrs Vickers mink coat was a key item of her wardrobe which she wore the Clery’s ballroom in the 1950s and 1960s.

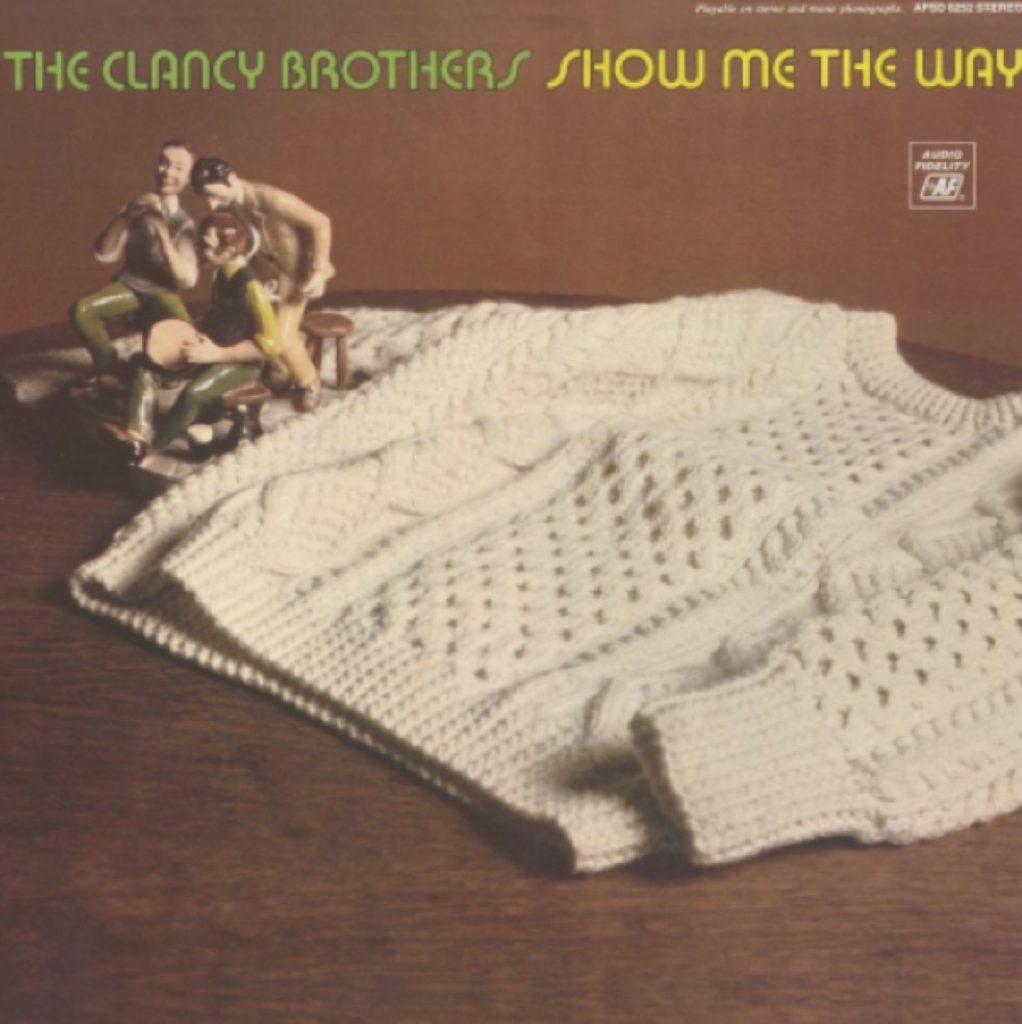

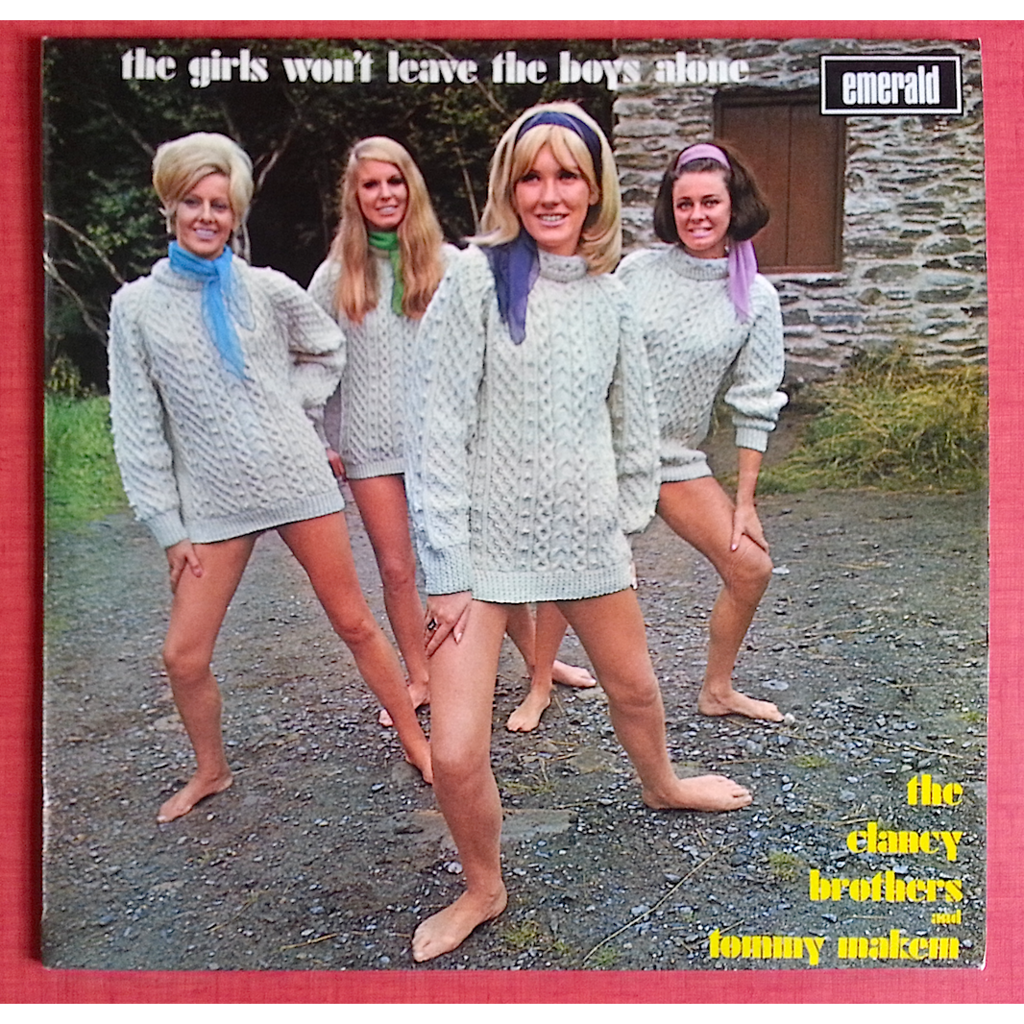

You can’t think of a Clancy brother without thinking of the Aran sweater and here the record cover showcases the iconic piece of knitwear as their emblem

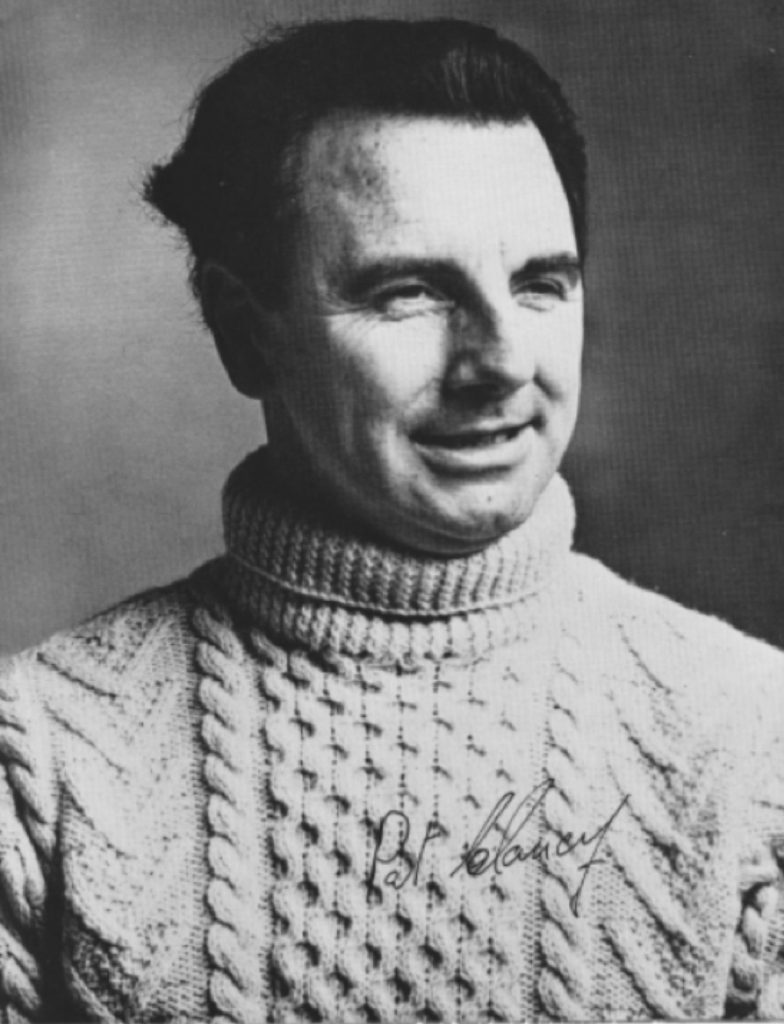

You can’t think of a Clancy brother without thinking of the Aran sweater and here the record cover showcases the iconic piece of knitwear as their emblem Paddy Clancy signed photograph wearing one of his infamous Aran sweaters which is submitted to the National Treasures exhibition by his wife Mary Clancy

Paddy Clancy signed photograph wearing one of his infamous Aran sweaters which is submitted to the National Treasures exhibition by his wife Mary Clancy Here a group of cool swinging 1960s chicks work the famous Clancy Brother’s Aran sweater on the cover of their album

Here a group of cool swinging 1960s chicks work the famous Clancy Brother’s Aran sweater on the cover of their album