by Ruth Griffin

National Treasures looks at history through a sporting, social, political, design and fashion lens. From Currachs to Crolly Dolls, bottles of Blue Nun to black mourning veils all of Irish life is reflected in its many guises through the objects on the show. Looking at heirlooms and personal artefacts tells a unique history of Ireland – a history coming from the people’s perspective. We know objects can tell powerful stories, but what about fashion? Can a prison uniform explain the harrowing consequences of the 1916 Rising? Can Sonia O’Sullivan’s running shoes tell us of her journey for Olympic gold? Or can a 1940s wedding dress tell us what women’s lives were like in Ireland at this time? Yes they can, because nothing gets closer to the body and to the zeitgeist than fashion. Captured in its make, cut, fabrication and styling is a story that can catapult you right into that moment of history in a truly tangible way.

Fashion is so much a part of life that its cultural significance often gets overlooked. Clothing has much to reveal about the time and place of its creation and the outer forces that gave it its shape and substance. As my fellow curator Donal Fallon has said in the series everyone’s home is a museum of a kind, so many interesting items that appeared on the roadshow have been sitting on mantelpieces or in glass cabinets in people’s kitchens and front rooms. But fashion is often kept hidden away in a hatbox or a wardrobe, kept and remembered but not on show.

The objects that arrived on my table unearthed from trunks and old tissue paper told me stories that ranged from the familiar – the Clancy Brother’s Aran sweater for example, to the rare – a prison blanket from the Long Kesh/Maze prison reinvented as an elegant three piece suit. What elevated these objects was that they had extra-ordinary owners who changed the item from something ten-a-penny to a National Treasure.

The objects I saw over the course of the series took me on a whistle-stop tour of what happened stylewise in Ireland. It showed concrete evidence of how we really dressed for romance, weddings, dances, discos, death, mourning and even prison over the last 100 years. So I’ve picked 3 very different objects from the show that explain how fashion has played a part in Irish culture and the wider world over the last 100 years, now its over to the objects themselves to do the talking…

1920s The Irish Flapper

The 1920s were an exciting moment in fashion history. A time when bright young things danced their way through the decade in bobbed hair and short flapper dresses. Although Ireland was a far cry from the hedonism of Manhattan or Mayfair. We did have some moments of flapper flamboyance in our new Republic of the 1920s, fashion was making itself known in small ways across the countryside with the arrival of cinemas to many towns and villages. What I found the most interesting when viewing objects from the roadshows was the ways in which fashion was present in even the most rural parts of the country and the pieces that were kept in memory of the wearer- usually because of their fondness for style.

1920s printed silk day dress with bias cut skirt, bow detail and drop waist silhouette submitted by Miriam Dunne.

Miriam Dunne brought to the roadshow a pretty 1920s day dress in delicate silk that belonged to her Mother, who was a Dubliner. The dress was kept because of a priceless memory of her honeymoon in Weymouth, Dorset in 1925 with her first husband. He sadly died of T.B. only a year after they married. Her daughter Miriam only realised the significance of the item after her Mother’s death, she discovered the dress and a rose gold bangle in pristine condition kept in a hatbox along with the photos of the honeymoon.

“She kept this dress in memory of her husband James Jackman who died of T.B. in 1926. She danced with her husband in the dress and treasured it as it captured this special moment in time for her. She married my father her second husband in 1938. We never knew my mother had a first husband until after she died. She was a very fashionable woman, myself and my sister were in awe of her and used to play with her clothes when we were growing up.” – Miriam Dunne

An item like this shows us how objects can take on a symbolic form, surviving for sentimental reasons and explains the importance of fashion as a marker of significant events in a person’s and particularly a woman’s life. This dress sums up both the exuberance and carefree days of the 1920s and Miriam’s mother’s life. A whimsical, flirty dress made for days walking down the pier without a care in the world.

Alison Killilea and her Great Aunt May’s black dress

A little (Black & Tans) dress

Other interesting objects that came to the roadshow from this period were the little black dresses from the 1920s-1940s submitted by Alison Killilea from Banagher, Co Offaly. These pieces were owned by her Great Aunt May Hynes. May was an active member of Cumann na MBan and was almost shot by the Black & Tans during a raid on her house in 1921. They show us how the trends of the time were played out in Ireland. The silhouettes and changing styles are all there from a drop waist 1920s dress, a 1930s dress trimmed in white lace (pictured above) and a 1940s fit and flare dress adapted from an earlier style.

Little black crepe dresses where made popular by Coco Chanel in the 1920s the trend spread like wildfire (and still exists) for their sophistication but also because they were a style that could be easily copied. It is remarkable too that dresses from this time survive. The fact that Alison still owns her Great Aunt May’s dresses is most unusual and it shows a reverence the lady herself had for clothes and her ancestors had for her by keeping them.

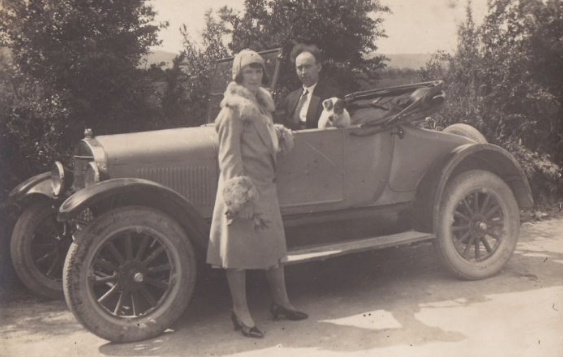

Alison’s Great Aunt May and Great Uncle Thomas and their little dog in their Model T Ford. Courtesy of Alison Killelea.

Looking modish with a motor car

And here we see photographic evidence of the tremendously fashionable May and Thomas Mileady posed in front of their motor car and dressed to the nines in the latest fashion. We see May in her cloche hat, fur trimmed drop-waist coat and neat heels. Thomas in a smart suit, shirt and tie. As a couple they must have caused a sensation in Banagher when they zipped down the main street in their Model T Ford (the first to own one in their village according to Alison), it shows us that in 1920s Ireland there were affluent pockets of the country, an emerging middle class who lived comfortable lives and were able to indulge in the latest fashions. It also gives a snapshot of the new Irelanders who were driving change, very stylishly.

Photograph of O’Connell Street in the 1930s. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Rocking a look under Clery’s Clock

We all know that the meeting point of Clery’s clock on O’Connell Street was where so many of Dublin’s romances began. But did you know that Clery’s was one of the first purpose built department stores in Europe (built in 1853), predating Le Bon Marche in Paris. It was one of Dublin’s key department stores, a fashionable destination not only for shopping but dancing and had a ballroom with a full-time orchestra working every night of the week.

The Clery’s ballroom of romance speaks of a different time and a different O’Connell Street. It’s hard to imagine now but the street in the mid-twentieth century was the Saturday night destination. The thoroughfare was lined with stylish hotels, department stores, cafes, restaurants and cinemas: The Metropole, The Carlton, The Ambassador and The Savoy. Dubliners dressed up to go out on Ireland’s main street and it was the place to see and be seen. The photographs of Arthur Fields (made popular by the Man on Bridge project) show us exactly how we dressed for the street from 1930-1980.

Photograph snapped by street photographer Arthur Fields of a 1950s couple on O’Connell Street.

And dances need dresses right? While the photographs and the buildings of O’Connell Street remain what of the clothes? At the roadshow in Dublin I was delighted to see a suitcase of clothes arrive by the son of a Clery’s staff member. His mother a Mrs Vickers worked in the store in the 1960s and 1970s. In the suitcase was flamboyant assortment of 1960s glamour some of which had been bought in the store. There were bright psychedelic prints, marabou feather hats and an all important mink fur coat by Vards of Dublin. This collection shows us exactly what was worn in the ballroom of Clery’s and speaks of that lost scene. It was a time when entertainment was about dancing, spending time with each other and music – and shockingly much of the dances would have been alcohol free. It’s hard to imagine such a scene existed but these clothes, photographs and memories explain why there was romance under Clery’s clock (it was the street you could bring someone on a date to). Mrs Vickers wardrobe and the legend of Clery’s clock is the last reminder of the dancing culture which was enjoyed by a generation of Dubliners. Today Clery’s department store lies dormant, it’s a good moment to remember its glory days and the important role it played in Dublin’s popular culture. We can only hope its future brings something bright and new that will entertain a whole new generation.

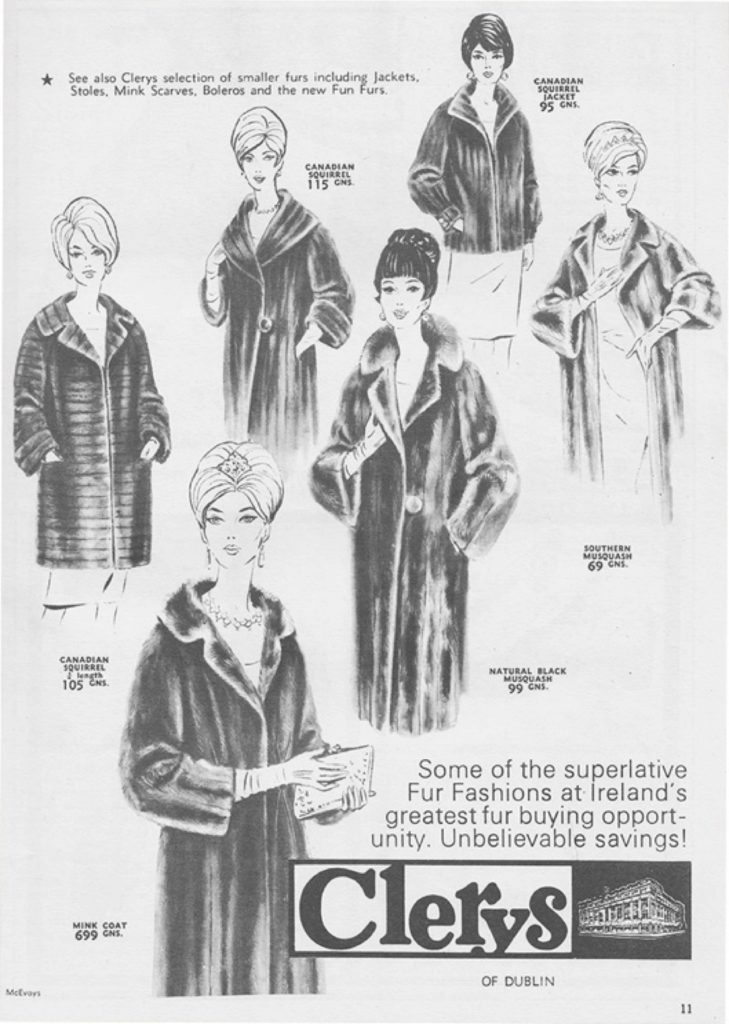

Fur was the epitome of glamour in mid-twentieth century Dublin. Here Clery’s advertise some ‘superlative fur fashions’. Mrs Vickers mink coat was a key item of her wardrobe which she wore the Clery’s ballroom in the 1950s and 1960s.

Fur was the epitome of glamour in mid-twentieth century Dublin. Here Clery’s advertise some ‘superlative fur fashions’. Mrs Vickers mink coat was a key item of her wardrobe which she wore the Clery’s ballroom in the 1950s and 1960s.

How the Aran sweater took on the world’s stage

“In the early summer of 1963, my husband Paddy Clancy and I were travelling to Mayo to visit my parents. We stopped off in Spiddal, to visit the famous shop Standuns. Paddy picked out a beautifully knitted polo neck jumper in genuine Aran wool. It was his favourite, he had many over the years but this one travelled many thousands of miles with him. He was tall and slim and the lines and patterning of the delicate knitting suited his trim frame. Sweaters had a tendency to become “lost or mislaid” on tour, he was lucky to have his favourite of all resting in retirement in his Irish home.” – Mary Clancy

There is no item of clothing more Irish than the Aran sweater. There is a magic about it which makes us believe it has been part of Irish culture for centuries. Strangely enough it hasn’t, it is a 20th century invention. It began with the Congested Districts Boards (a board devised to alleviate poverty in the most stricken areas of Ireland) who brought fishermen from Scotland and the Channel islands to help bring improvements to fishing on the Aran Islands. The Scottish fishermen who came to the islands wore blue geansais and the fishermen’s wives who accompanied them on the trip taught cable knitting techniques to the islanders. It is from these events that the Aran sweater was born. It may seem like a disappointing beginning but I think the origins of the garment doesn’t matter, what matters is what happened next, the Aran knit evolved from great Irish ingenuity and creativity, from the late 1890s when the cable technique was introduced to the 1920s over 70 unique Aran stitches were developed by the talented knitters of the island. This shows great innovation and design, taking one idea and making into something totally new. However, the development of a knitting technique alone is not enough to launch an item like this into the common fashion vernacular. It needed a cultural icon (or two) to bring it onto a global stage and it got it in the mighty form of the Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem.

The Clancy Brothers. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives

The Clancy brothers were a huge presence on the American Folk revival scene of the 1950s and 1960s, their influence was immense in the USA, Bob Dylan cites them as an early influence and in Ireland their music was of even greater importance gaining popularity during a time in which folk music had been mostly forgotten. This revival of folk music brought with it unexpectedly a revival of Irish folk dress when they used the Aran sweater as their trademark on stage.

The story goes that it was a bitterly cold winter in New York City and back home in Carrick-on-Suir the Clancy Brother’s Mother knitted up four Aran sweaters for her sons and sent them by post. The brothers wore them at a Greenwich Village folk club, and it quickly became their look. When they played the Ed Sullivan Show in March 1961, their pristine knitwear made them the most famous Irishmen on earth.

Seen in this context the Irish sweater was introduced to a new generation as cool and modern with a folk/bohemian edge. A rush of celebrities were seen wearing it in the years that followed. Its practicality and its coolness meant it was an easy piece to introduce into your wardrobe. Designers began to include the piece in their collections. And just like how Coco Chanel reinvented the French fisherman sweater (the striped breton top) into the epitome of chic the Aran sweater has also been consistently reinvented over the decades since the Clancy Brothers with designers from Lainey Keogh, Ralph Lauren and Jean Paul Gaultier all featuring them in their collections.

Last year the Aran sweater was chosen as one of the world’s most iconic fashion designs for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York city for its exhibition “Is Fashion Modern” because it is considered a powerful and enduring example of 20th century clothing. And more recently at the Autumn Winter 2018 shows this spring an Aran knit was draped on the back of each attendees seats at the Alexander McQueen show, showing us the look of the Irish, made cool by the groundbreaking Clancy’s brothers continues to be very much in vogue in 2018.

I felt very privileged to see the ‘real’ Clancy Brother’s Aran knit it person and to have the Clancy Brother’s wives arrive to tell their stories at the Cork roadshow. It made the objects into living, breathing things. Hearing the story of the sweater and of the brothers from the family gave extra insight into these remarkable men. And just to show us the importance of the Aran knit Mary Clancy, Paddy’s wife was sporting one of her own in honour of her man on the day.

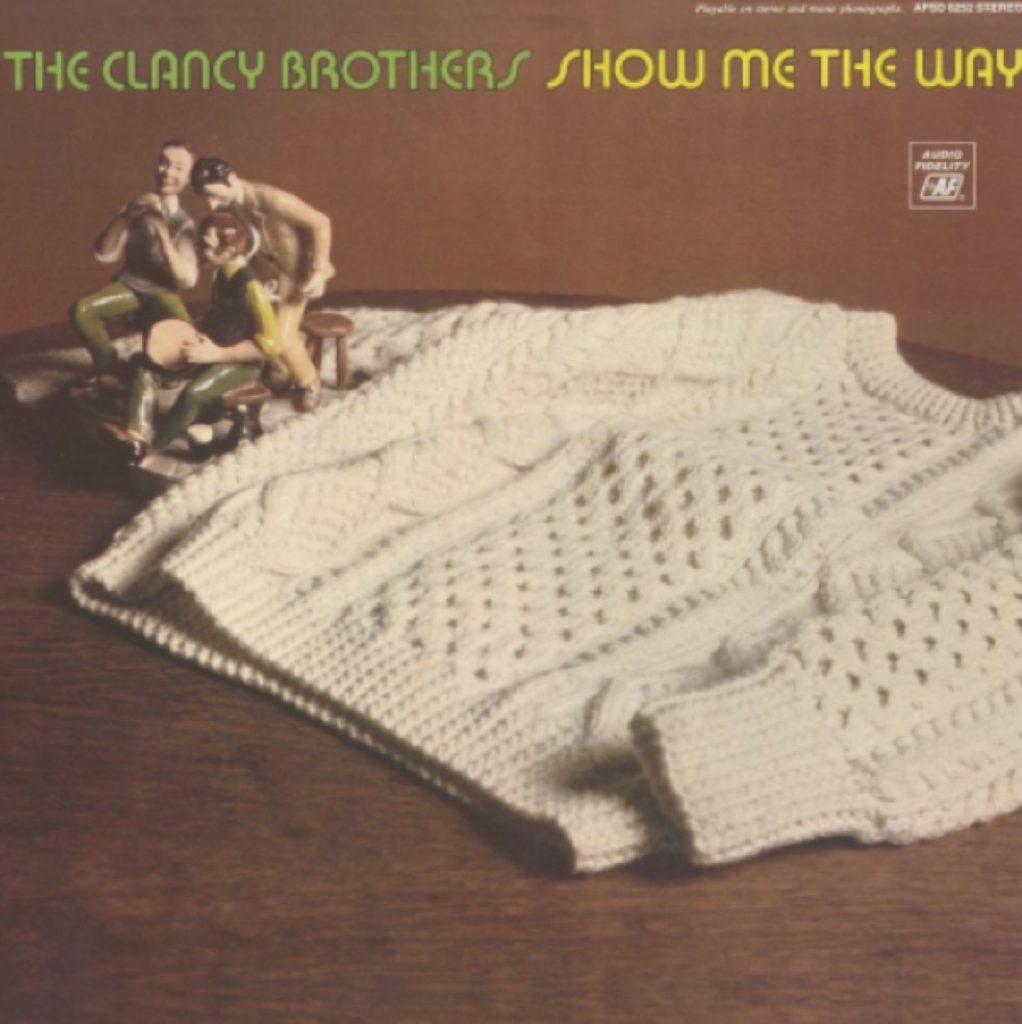

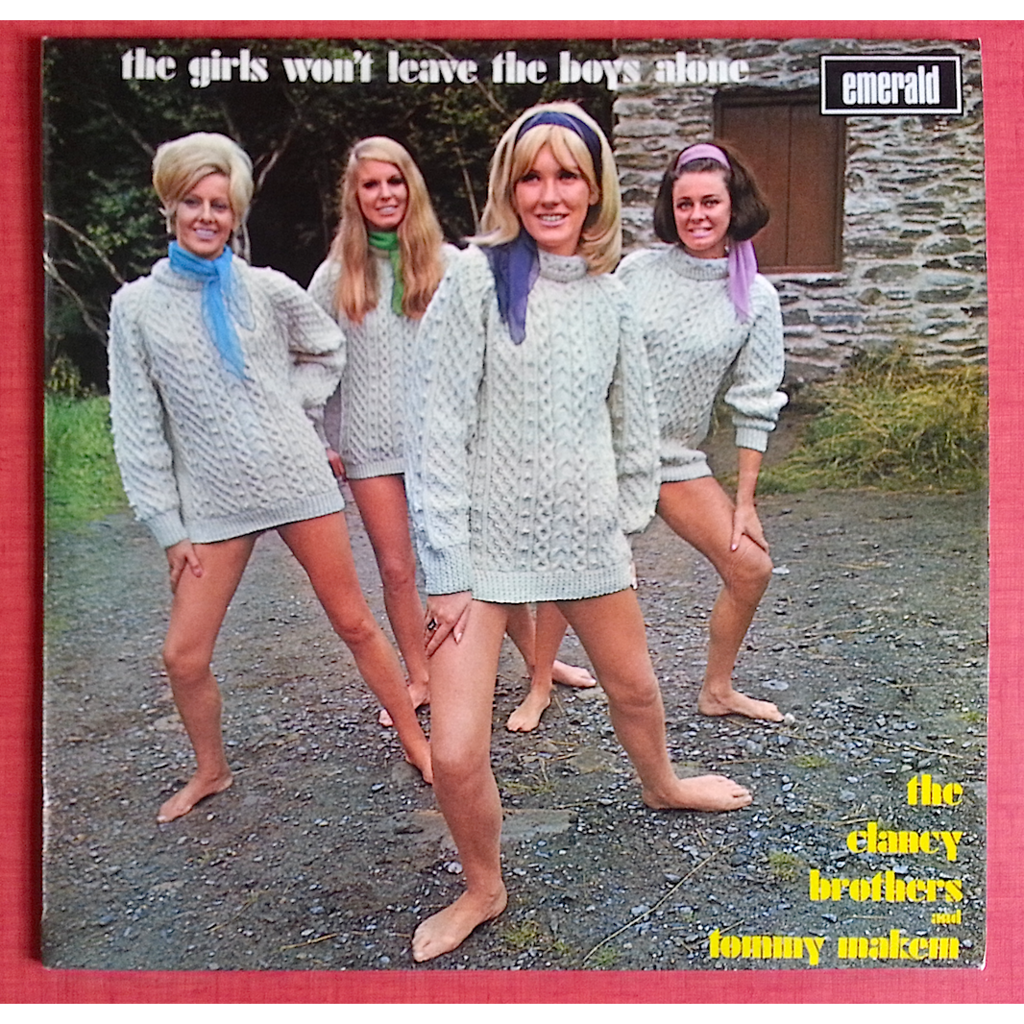

You can’t think of a Clancy brother without thinking of the Aran sweater and here the record cover showcases the iconic piece of knitwear as their emblem

You can’t think of a Clancy brother without thinking of the Aran sweater and here the record cover showcases the iconic piece of knitwear as their emblem

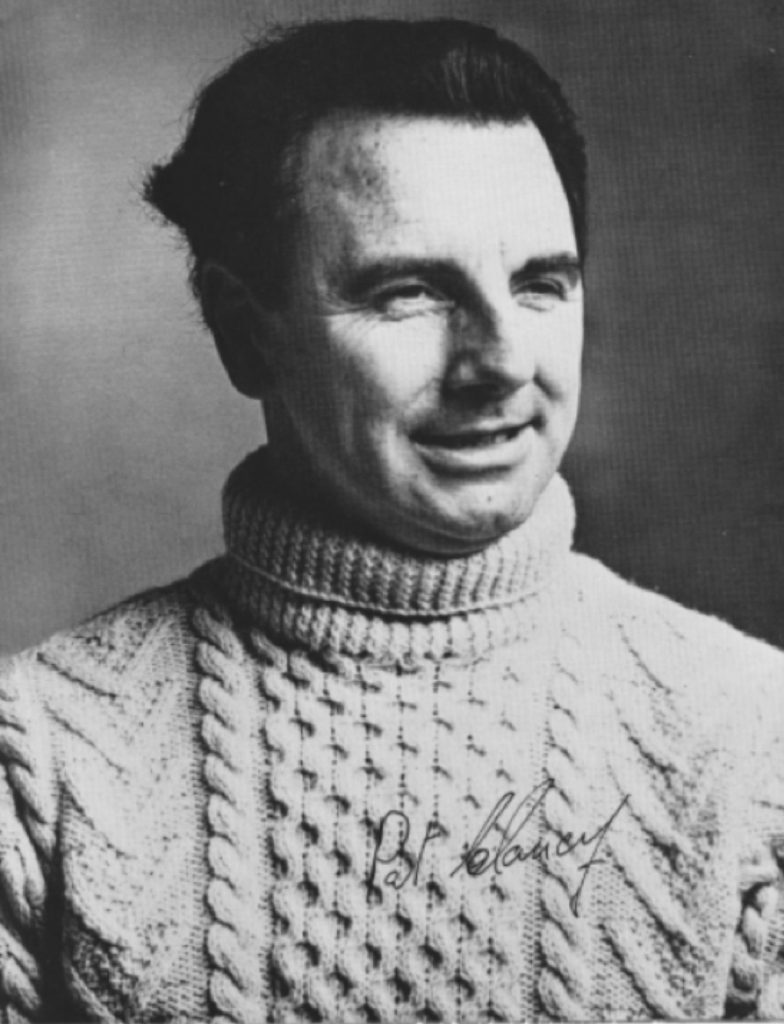

Paddy Clancy signed photograph wearing one of his infamous Aran sweaters which is submitted to the National Treasures exhibition by his wife Mary Clancy

Paddy Clancy signed photograph wearing one of his infamous Aran sweaters which is submitted to the National Treasures exhibition by his wife Mary Clancy

Here a group of cool swinging 1960s chicks work the famous Clancy Brother’s Aran sweater on the cover of their album

Here a group of cool swinging 1960s chicks work the famous Clancy Brother’s Aran sweater on the cover of their album

Laurence McKeown: From Prison Blanket to Three Piece Suit

A prison uniform marks you, and it’s designed to. The idea of what prisoners have worn over the years has gone into our collective unconscious from films and cartoons of the arrow printed uniforms of 19th century England, the black and white stripes of Nazi Germany and more recently the orange uniform of hit US series ‘Orange is the new black.’

Laurence McKeown came to the National Treasures roadshow wearing what was one of the most extraordinary objects of the show – a prison blanket which had gone through a transformation into a three piece suit, complete with bow tie, waistcoat and scarf. And within the make of the very fabric of this suit is a story of the struggles in Northern Ireland in the late 1970s and 1980s. Not all objects can tell the bright side of Irish life and this object certainly talks of one of our darkest hours, but it also shows how fashion has the ability to take you from two extremes.

In 1977 McKeown had been sentenced to life imprisonment in the Long Kesh/Maze prison for his activities in the IRA. At this time the republican prisoners’ status as political prisoners, known as Special Category Status, had begun to be phased out. Among other things, this meant that they would now be required to wear prison uniforms. The prisoners refused to accept that they had been administratively designated as ordinary criminals, and refused to wear the prison uniform.

And so the prison blanket protest began, this act of defiance, of not wearing the prison uniform but only wearing the prison blanket for warmth was called going ‘on the blanket’. Photographs of the time show prisoners with the long hair and beards of the late 1970s and prison blankets hung over the shoulders of their naked, emaciated bodies. This protest was the precursor to the Hunger Strikes of 1981. After the death of ten men including Bobby Sands during the Hunger Strikes a change was made to prison policy and all paramilitary prisoners were allowed to wear their own clothes at all times.

Laurence was present throughout all of these events and survived. He was released from prison in 1992, and since then he has written 2 books Nor Meekly Serve My Time: The H-Block Struggle 1976–1981 about this particular moment in Irish history. But it is in his very dress he has chosen to commemorate his own personal and political struggle. He said: “I had been given an old prison blanket when the H Blocks closed and it had been lying in the attic for a long time. I decided to have it made into items of clothing which would look elegant and then ask former Blanket Men and Women to wear them and have their photographs taken by a professional photographer.” The result is something quite remarkable an anti-establishment garment of protest transformed into the most elegant socially accepted form of dress – a tailored suit – and when he wears it he challenges us with his presence to remember this particular time in history in his own unique way.

So to conclude, we have seen how fashion objects are far from frivolous. They allow us to encounter the past first hand and to put ourselves quite literally in the shoes of those who wore, refused to wear, made, used, or enjoyed them.

So tune into National Treasures on RTE 1 across April. You’ll see some of these objects and much more. And come see them in person at the National Museum of Country Life in Turlough Park in Mayo, I guarantee it will inspire you to look deeper at the history of objects which exist all around you.

Ruth Griffin, Fashion Historian

Ruth Griffin is a fashion historian, writer and blogger with a BA in Fashion Design from the National College of Art & Design in Dublin and a Master’s degree in History & Culture of Fashion from London College of Fashion. She has developed her knowledge and expertise in fashion history for over a decade by researching fashion and its relationship to the city of Dublin. She runs a popular programme of fashion history tours in Dublin every summer and a blog that uncovers the often lost history of Irish fashion design, businesses and icons. She is regularly asked to speak on radio and TV and at Dublin’s favourite cultural institutions from the National Gallery of Ireland, the National College of Art & Design and The Science Gallery at Trinity College Dublin.