by Donal Fallon

The events which occurred in Ireland between 1912 and 1923 constitute a revolution, or at least a moment of revolutionary potential. If the state that emerged reflected the aspirations of many in that period remains a debated subject, especially as we move towards the centenaries of the foundations of both the Irish Free State (today the Republic of Ireland) and the state of Northern Ireland.

Helena Molony, a talented Abbey Theatre actor and committed revolutionary in the ranks of the Irish Citizen Army, later lamented how “we saw a vision of Ireland, free, pure and happy. We did not realise that vision. But we saw it.” To others, the birth of the state was a fitting culmination to the period. Government minister Kevin O’Higgins wryly insisted that the Irish were the “most conservative-minded revolutionaries that ever put through a successful revolution.”

In trying to create a canvas of Ireland in the last century, we found the revolutionary period an essential component of the story. In the spirit of National Treasures, the items which came forward provided new perspectives on a well-known national story.

By 1918, the very form of the Irish revolution was shifting. The 1916 Rising had been a minority affair, largely confined to Dublin with some action in Galway and Wexford. Viewed largely either through the lens of outright hostility or curious bemusement by the civilian masses, first hand oral testimonies from participants point towards the difficult week endured. One bewildered Volunteer at Jacob’s biscuit factory recalled that “the residents of Fumbally Lane even followed retreating Volunteers to Jacob’s, knocking off their hands and kicking them – and then tried to attack the Jacob’s garrison by attempting to smash down the gate and attempting to burn it down with a sack doused in paraffin.” This behaviour wasn’t unique to Dublin; Volunteer Thomas Courtney in Galway was so horrified by the lack of support for the populace there towards the rebellion that he recalled Galway to be “the most shoneen town in Ireland.”

British mishandling of the Rising, and increasing hostility towards the seemingly never-ending war on the continent, played no small role in creating a newly radicalised populace. At Easter 1917, the first anniversary of the Rising was marked by large scale and illegal commemorations across the country, with a tricolour raised over the ruins of the General Post Office. The fear of conscription in 1918 brought hundreds of thousands of people into political radicalism, and swelled the ranks of the IRA. The Catholic Church, the trade union movement, Sinn Féin and others actively resisted the threat of conscription together, pledging to do all in their might to keep Irishmen from already infamous battlefields.

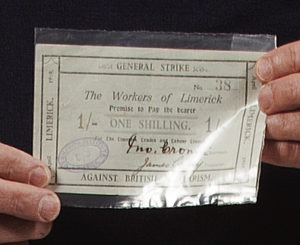

Among the more curious social history items relating to this period in the National Treasures online archive are currency produced during the Limerick Soviet of 1919, the centenary of which will take place next year. Essentially a protest against the British declaration of a “Special Military Area” under the draconian Defence of the Realm Act, this protest, from 15 to 27 April 1919, saw a Workers’ Soviet essentially running the city of Limerick, distributing food and printing its own currency. It was a powerful demonstration of the impact of events in Russia on popular political terminology and discourse, and one of around one hundred so-called Soviets in Ireland during the revolutionary years. In Westminster, this was pointed to as “an example of the effect of Communist Propaganda from Moscow.” The currency was submitted by Gerry Casey, whose great grandfather was a leader of the Soviet. The idea of workers taking the Irish revolution into their own hands didn’t always sit well with republican revolutionaries; legendary republican leader and later Fianna Fáil Minister Dan Breen lamented the “supporters of the Red Flag regime” who tried to create Moscow and Leningrad in Mallow and Longford.

A three year guerrilla war, like that fought in the hills and valleys of rural Ireland, could only be maintained with the support of a civilian populace. Items in the National Treasures collection that reflect that include a striking grenade that was produced locally in Cork, brought forward to the collection by Barry Curtin. The mould in which the grenade was made was constructed subversively by workers at the Ford factory, utilising their skills for very seditious purposes. While IRA HQ in Dublin included dedicated logistics and munitions experts, the war could only be sustained thanks to the network of covert munitions factories that sprang up in rural Ireland.