by Dr Richard McElligott

Sport has always been a powerful platform for the expression of identity. We see this in the crowds decked in their parish colours who flock to county championship matches the length and breadth of Ireland, or the legion of supporters clad in green that follow our national soccer and rugby teams across the world. Yet Ireland is also a country where sport has always been surrounded by wider questions of political and cultural allegiance.

Belfast Celtic

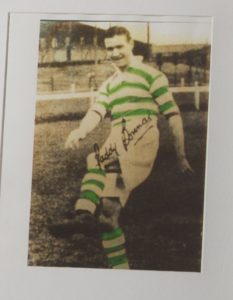

Paddy Bonner’s Belfast Celtic Jersey (submitted by John Boyle) is an object which represents one of the most significant but largely forgotten forces in the history of domestic soccer on this island. Founded in 1891, in the deeply nationalist Falls Road area of West Belfast, the club took inspiration from the Glasgow Celtic team established by Irish nationalist emigrants three years previously. During their fifty-eight years of existence, Belfast Celtic became one of the most celebrated and successful teams in Irish soccer, winning fourteen Irish League titles and eight Irish Cups. But more than their on-field success, Belfast Celtic was the sporting embodiment of the city’s nationalist community and a powerful emblem for its discriminated Catholic working class.

The deeply sectarian atmosphere of early twentieth-century Belfast was reflected in Celtic’s bitter rivalry with the Unionist and protestant aligned Linfield FC. Often the broader political controversies of the period were evident on the field of play. In autumn of 1912, the Home Rule Crisis erupted as mass Unionist resistance to the measure, which would grant a Dublin parliament a limited degree of Irish self-government, was organised across Ulster. That September, serious riots broke out during an Irish League game between Celtic and Linfield. Following the bitter exchanges of sectarian songs and chants between the rival fans, the Celtic fans unveiled a giant green flag and charged at Linfield supporters flying a large Union Jack. Over fifty people were injured.

Yet despite their deep divisions, the Nationalist and Unionist communities of Belfast shared the trauma of the First World War and its impact on Ireland. With the War’s outbreak, the Irish Football Association took the decision to suspend all competitions and during the course of the conflict over 1,800 Celtic members and supporters enlisted, many never to return. Though the Great War gave both communities a shared communal experience, the political turbulence which enveloped Ireland in the years following 1916 frequently impacted on Celtic’s sporting activities. As the War of Independence unfolded in southern Ireland, violent disturbances broke out at an Irish Cup match between Celtic and Glentoran in March 1920 in which an on-duty police officer was shot and severely wounded. Sectarian riots continued to plague football games in the city throughout the summer of 1920, resulting in eight deaths alone between August and October. As a result, Belfast Celtic was forced to abandon the 1920 season and did not re-join the Irish League until 1924. By then over 450 people had been killed in the mini civil war which took place on the streets of Belfast as the new Northern Irish state was established after December 1920.

Belfast Celtic dominated the Irish League in the inter-war period, winning ten titles in fifteen years. Despite this success, the club continued to be the victim of sectarian motivated attacks. Matters came to a head during a match with Linfield on 26 December 1948. Following a late equaliser for their team, Linfield fans stormed the pitch and assaulted three Celtic players including their forward, Jimmy Jones, who was kicked unconscious and suffered a broken leg.

The club’s management took the painful decision to withdraw from all domestic competitions at the end of the current season because they felt they could no longer guarantee the safety of their players or supporters given widespread accusations that the police on duty at the match did nothing to intervene against the Linfield supporters. That summer the club undertook a ten-game tour of North America where they enjoyed huge support among the Irish nationalist diaspora. One of the club’s most memorable moments came on 29 May, when they defeated a star studded Scottish national side 2-0 in front of 15,000 supporters in New York. Nevertheless more controversy was generated when pictures of the team parading behind the Irish tri-colour were reprinted in the Belfast Telegraph.

Belfast Celtic never again returned to competitive action, but the club tried to keep itself viable by travelling the world playing several friendly games, including a match against Glasgow Celtic in 1952. The team’s final appearance occurred in a testimonial game in 1960, after which Belfast Celtic formally disbanded. Today a small plaque and museum near Celtic’s original ground, where Paddy Bonner’s jersey is displayed, are the only remnants of the club’s proud history.

Find out more about John Boyle’s submission to the National Treasures project here: https://nationaltreasures.ie/submissions/Q999FM

Dr Richard McElligott is a native of county Kerry and a lecturer in modern Irish history in University College Dublin. Richard has published widely on the history of Irish sport and also on the Irish Revolutionary period, 1912-1924. He is the author of Forging a Kingdom: The GAA in Kerry, 1884-1934 (2013) and editor of A Social and Cultural History of Sport in Ireland (2016).