by Roisín Higgins

Each time I move house I take with me a box full of letters that I have received or never sent. They are fragments of my younger self that I keep because they contain memories of homesickness and heartbreak, adventure and love. They are a good example of how objects carry meaning and feelings into the present. When I joined the team at ‘National Treasures’ I hoped to find things that captured the emotions and rhythms of Ireland’s past. I was sure that we would better understand our history and society by listening to the widest range of its individual stories. In each city we visited there were objects that were personal and yet cast a light on significant aspects of the country’s past.

The Handwoven Picture Box

Dolores Kelly brought a little box her mother made while in a TB sanatorium in Peamount Hospital, Co Dublin in the 1940s. Dolores’s mother was in the sanatorium for three years and throughout this time was only allowed to see her child through a glass partition. The box is a treasured part of the family’s story and is used to keep letters and mementos gathered in the years since it was made.

Almost every family in Ireland has a story about Tuberculosis. It was one of the major causes of death in the 1940s and it was not until the introduction of streptomycin and other antibiotics that mortality rates began to decline in the 1950s. When he became Minister for Health in 1948, Noel Browne introduced free screening for TB and spearheaded the building of new hospitals and sanatoria. Browne had himself suffered from the disease, and both his parents died of it.

Tuberculosis was infectious and therefore it was attended by enormous fear, and the treatment in sanatoria sometimes meant years of separation. Therefore TB affected entire families very deeply and the memory of this has been passed down through generations. Dolores’s little hand-made box contains this much larger story.

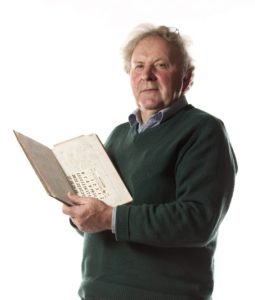

In Cork, I met Thomas Wall. He had a letter which he had not received until many years after it had been sent. The letter was from his aunt, written to him while he was a child in Glinn Industrial School in Limerick, asking if she could come to visit. Tom found the letter among records left by the Christian Brothers who had run the school. He salvaged some material after the school was closed in 1966 (records of the food children were given, the documents they signed on release), and in the process found his own letter.

The industrial school system is among the most shameful parts of Ireland’s recent past. At least 173,000 children entered industrial and reformatory institutions between 1936 and 1970. Poverty was the defining factor in their incarceration. The average age of the boys committed to Glinn was nine years and 10 months, and the average sentence was five years and eight months. The Commission to Investigate into Child Abuse (set up in 1999) found that Glinn had a severe systemic regime of corporal punishment; that it failed in its fundamental requirement to provide care, education and training for the boys and that the Department of Education had failed in its supervisory duties.

It might seem impossible to include an item relating to industrial schools in a programme called ‘National Treasures’. How could we possibly treasure these institutions? However, it was really important that we didn’t edit out these parts of history. If Tom hadn’t come along we wouldn’t have been able to tell this story. We were relying on members of the public to bring their history to us. In keeping these records and sharing them here, Tom has done us all a service.

Nowhere was it more important to make sure we conveyed the complicated messiness of history than in Belfast. For me a bed of nails summed up perfectly the exuberance of a city amidst the sharp edge of conflict.

Nora Greer arrived with a variety of colourful objects from the Belfast Community Circus School. She had been married to one of its founders, Mike Moloney, who sadly died in 2013. Mike was an Australian who arrived in Belfast in 1981. Along with his friend Donal McKendry he began running workshops in areas like Tiger’s Bay, the New Lodge and Travellers’ camps on the Glen Road, eventually establishing the Community Circus School in 1985. They worked with people who didn’t necessarily fit into the mainstream and taught them how to walk on stilts, juggle and eat fire. Almost everyone he taught said Mike believed in them when they weren’t able to believe in themselves.

To publicise the Community Circus, Mike would lie on his bed of nails to the amusement and bemusement of those who passed by. During the worst years of the Troubles he brought people together by acting the clown.

Mike Moloney went on to become Director of the Prison Arts Foundation. An Arts Bursary Fund for former prisoners set up in Mike’s name is designed to recognise and support the possibility of change. Mike’s bed of nails represents a similar belief.

Dr Roisín Higgins is a Senior Lecturer in History at Teesside University. She is an expert on historical memory and has published widely, including her award-winning book Transforming 1916: meaning, memory and the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising. Roisín is a founding director of the Irish Association of Professional Historians.